Competence in wood is in Finns’ DNA – A review of contemporary Finnish wood architecture

ALA Architects, Oodi, photo: Tuomas Uusheimo

In the old days, Finns knew how to build their own houses. However, contemporary wood architecture that utilises digital solutions and new industrial approaches also requires brand-new competence. Tarja Nurmi, an architect and architecture journalist, writes about today’s trends in Finnish wood architecture.

The brothers depicted in The Seven Brothers (1870), the beloved novel by Finland’s national author Aleksis Kivi, are often considered somewhat simple due to their stubbornness and illiteracy. Actually, the brothers are astonishingly multi-talented: they know how to cultivate land, hunt and fish – and even build their own houses.

Indeed, the traditional Finnish culture has included the ability to use the tools needed in wood construction. Later, these houses, built with their residents’ own hands, may have been taken apart one log at a time, moved elsewhere and re-erected. There was no need to talk about recycling and reuse; after all, all this was self-evident in scarce conditions. Similarly, it was a matter of course that the log houses, sealed and insulated with moss, were very natural indeed without a need to separately consider their ecological sustainability.

However, in the industrialised and modernised world, including in Finland, we must relearn some basic things. We want to construct with wood again – and we want to do it as well as possible. While industrial construction lends itself to wood construction, we must also not forget the methods of old times: traditional wood construction craftsmanship is also a resource. In fact, since the 1990s, students at the Aalto University's Department of Architecture (formerly known as the Helsinki University of Technology) have been learning about the characteristics of wood and wood construction skills in the special Wood Program.

One of the most well-known buildings originating from the program is the Helsinki Zoo Observation Tower Kupla (2002), a bubble-shaped web-like structure designed by architect Ville Hara, then a student at the university and later the founding partner of Avanto Architects. The young architect also won the significant European AR+D Award for Emerging Architecture prize with his observation tower. One of the latest buildings originating from the students’ efforts at the Wood Programme is Little Finlandia* (Jaakko Torvinen, Havu Järvelä, Elli Wendelin, 2022) in Töölönlahti, Helsinki, located in front of the iconic Finlandia Hall designed by Alvar Aalto.

The impressive rise of new wood architecture

Contemporary wood construction and architecture have started to take wind in the new millennium. This has required new kinds of competence and attitudes, not only from designers but also from clients and constructors.

In the early 2010s, a new building was completed in the Helsinki city centre that definitely stands out from its environment thanks to its object-like oval shape and wooden façade. The Kamppi Chapel (K2S Architects, 2012), also known as the Chapel of Silence and owned by the Parish Union of Helsinki is intended for spending quiet time independent of religious beliefs.

In housing architecture, Puukuokka I (OOPEAA – Office for Peripheral Architecture, 2015), a wooden block of flats located in Jyväskylä attracted lots of attention and won the Finlandia Prize for Architecture. The whole consisting of wood-frame blocks of flats implemented in three phases was completed in 2018.

Wood is also given great visibility in one of our most well-known works of contemporary architecture, Helsinki Central Library Oodi (ALA Architects, 2018). The entrance building of the Helsinki Airport (2021), also designed by ALA, has a similar, impressive dropped ceiling that reaches into a wood-covered awning. The building was awarded the Finnish Wood Award in November 2022.

One of Finland’s most exciting and sympathetic work environments is found in an office building in the Wood City* block constructed of wood. It stands as evidence of how an internationally successful game company is glad to also accept a wood building as part of its trademark. The final phase of Wood City (Anttinen Oiva Architects, 2019–2024), a block combining office and housing construction located in the new Jätkäsaari neighbourhood in Helsinki, is currently under construction.

Traditional log structure also works in contemporary architecture

New-generation wood construction has produced beautiful and pleasant daycare and learning environments. CLT is often utilised in these buildings, but we also know how to rely on more traditional log structures. As late as in the early 2000s, log construction seemed inconvenient due to a variety of regulations and interpretations by local authorities, but in 2016, the world’s biggest log school was completed in Northern Finland (Pudasjärvi Log Campus, Lukkaroinen Architects). Monio* (AOR Architects, 2023), an upper secondary school and multi-purpose building with a log structure currently under construction in Tuusula will be even bigger.

A two-floor solid wood building with four flats is currently under construction in Helsinki and will match the characteristics of traditional wood buildings as far as possible. The use of glueless solid-wood structure, clay plastering and wood fibre for isolation and relying on natural ventilation will help achieve a healthy building that is easy to repair with an expected life cycle of up to 400 years. The house was designed by Livady Architects, a firm specialised in healthy and sustainable construction that preserves the environment.

In addition to a careful design process, there is a need to invest in high-quality timber in log buildings. A turf-roofed hut, which was implemented based on a freely available series of drawings of overnight huts by architect Manu Humppi, was carved of close-grained and sturdy wood. The auxiliary building of an old family manor has been built on a natural rock foundation and no plastics or any other synthetic materials have been used in its construction. We can translate the lessons learned from the old construction methods to today – starting with making sure that we have enough slowly-growing, close-grained wood fit for construction growing in our forests.

Sports and wellbeing within the confines of wood structures

Wood is a natural choice for the material used in outdoor recreation structures. Any structures in the natural environment, such as bridges, duckboards or platforms and towers intended for observing the landscape, must be ecologically and aesthetically sustainable and support the experience of the wilderness. Therefore, it comes naturally to build them out of wood. A good example of this is the Nattours nature trail* with birdwatching platforms designed by the architects of Studio Puisto and the Nomaji Landscape Architects in Vanhankaupunginlahti, Helsinki (2017, 2022).

Building in the wilderness also sets challenges to the design process that differ from the norm. When Manu Humppi, an architect and experienced hiker, was designing the new Rautulampi Wilderness Huts (2021) for a national park located in Lapland he was tasked with finding a solution to how to realise construction in the untouched wilderness while taking weather-resistance and natural conditions into account. The solution was prefabricated CLT elements transportable on snowmobiles and tracked vehicles.

Throughout the times, wood has also been used in sports venues in Finland. A more recent example of sports venue construction is the steel and wood-structured canopy of the Rovaniemi Sports Arena Railo (APRT Architects, 2015), which was awarded the 2016 Finlandia Prize for Architecture. Meanwhile, the Helsinki Olympic Stadium, a prime example of white Functionalism, prides itself in its new wood-clad canopy covering the stands (K2S Architects & NRT Architects, 2020) – the recipient of the 2020 Finlandia Prize.

Ähtäri, a town in Southern Ostrobothnia, has decided to commission a wooden swimming hall* (Studio Puisto, 2023) that would serve the local residents and the adjacent hotel. While wood-built hall spaces have been reintroduced to new sports venues, there is also a need for more masterworks by brilliant structural designers in today’s wood architecture. One highly interesting and ambitious wood construction can be found in Kotka, where the lobby roof structure of the Satama Areena* event centre designed by ALA Architects (2023) is implemented using a wooden suspended structure.

Starting in the 2010s, a trend for building attractive public saunas has emerged in Finland. The Löyly Public Sauna and Restaurant (2016) on the shoreline of Hernesaari, Helsinki, heralded the trend. The building shaped like a rocky island and screened by wooden bars was designed by Avanto Architects. The Lonna Sauna (2017), located on an island at the front of the Helsinki city centre and designed by OOPEAA, represents more traditional log construction. A new, wood-framed lakeside sauna and restaurant building Kiulu* (Studio Puisto, 2022) was just recently completed in Ähtäri, and another sauna-restaurant designed by the same agency is currently under construction in Kuopio.

International trends

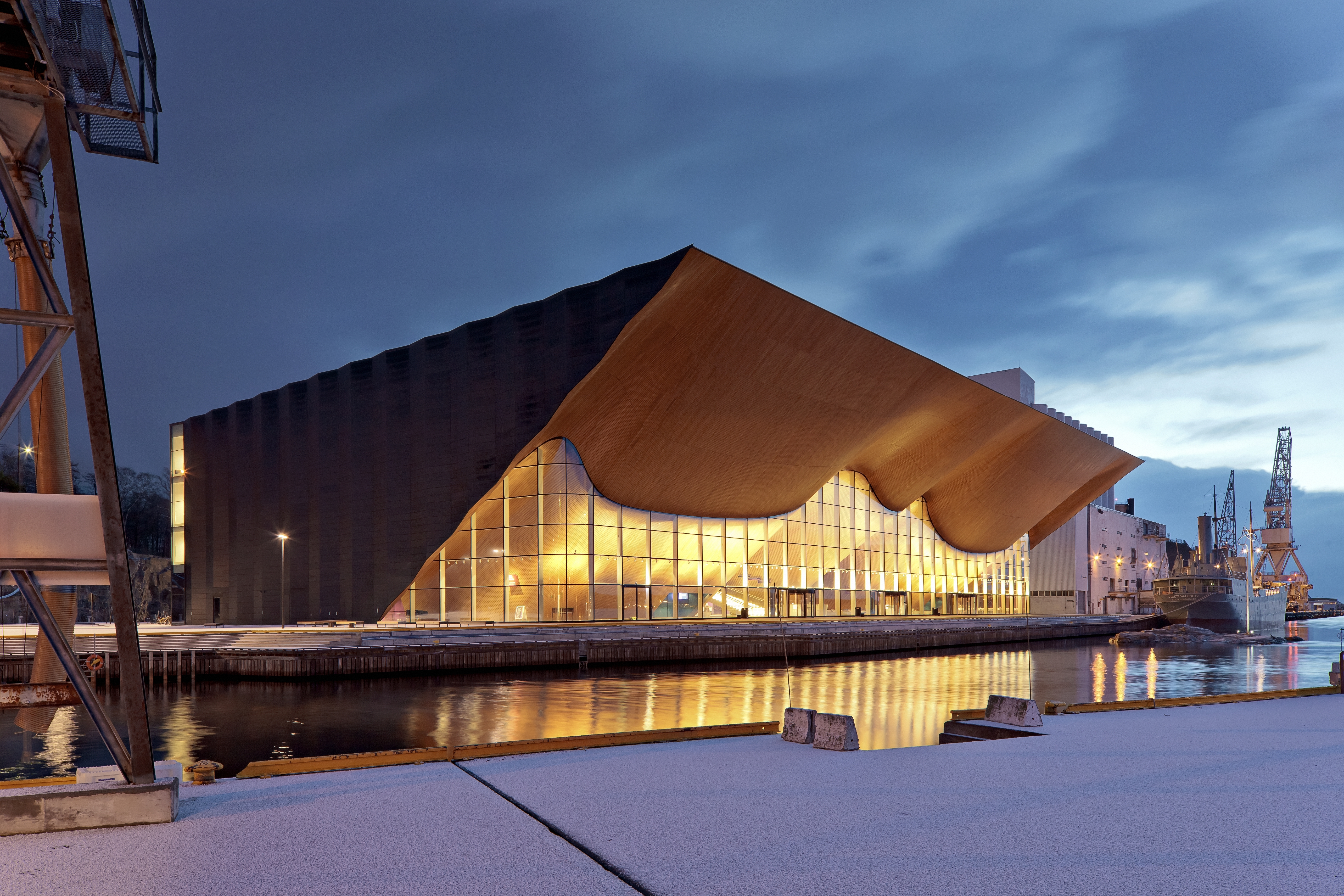

Wood architecture trends come to Finland from the world – and vice versa. In 2005, ALA Architects, who later designed the Helsinki Central Library, made their breakthrough directly to the international arena by winning an architectural competition to design a theatre and concert hall in Kristiansand, Norway. With its massive wooden facade, Kilden Performing Arts Centre (2011) paved the way for the agency’s recognisable architectural expression.

While the winning entry to the Serlachius Art Museum competition, the wood-framed Gösta’s Pavilion* (2011), was by an agency from Barcelona, and the same team Mendoza-Partida Architectural Studio & BAX Studio also designed the newly completed Art Sauna* (2022) on the museum premises, the buildings were implemented in collaboration with a Finnish partner, architect Pekka Pakkanen, and stand also as a strong representation of Finnish competence in architecture and wood construction.

The Finnish architect Olavi Koponen has been running his agency in Grenoble, France for a long time and designs wooden buildings with a personality both in France and Finland. For example, the Villa Riviera located along Lake Saimaa and designed for a private client is beyond compare. The building has been adapted to nature with a great amount of respect, and even the lichen terrain surrounding the building has been left untouched.

Nevertheless, the trend adopted in Finland from Central Europe to leave wood-covered façades untreated – or stain them nearly black – does not always suit the Finnish environment. Another trend has been to combine undyed wood with vivid, even zesty colours in public buildings. By contrast, Finnish wood buildings have traditionally been treated with red ochre or painted in a soft palette.

An example of the use of such a classic colour palette is Villa Oivala designed by architect Oiva Kallio and completed in the Helsinki archipelago in 1924. The beautiful example of the 1920s Nordic Classicism has been painted in a yellowish-grey tone from the outside. A special feature of the building hides in its atrium-like inner courtyard, which has been painted in a bright, Mediterranean-esque blue. The building is currently owned by the Finnish Association of Architects, and it has been studied and carefully renovated by Livady Architects for a decade now. Livady’s masters in traditional methods have also carved structural elements in the old style to replace broken ones.

What is the language of new wood architecture?

We need more new-generation carpenters and skilled workers with furniture carpentry skills to create carefully made details. The use of wood elements and CLT panels should not result in overly simplified aesthetics. New, more subtle details should be developed for the new wood construction methods so as not to settle for minimalism only.

Not unlike how the seven brothers with versatile skills and speaking a lively tongue created by the author Aleksis Kivi learned to read at the end of his narrative, a brand-new and lively language of contemporary wood construction can also emerge in Finland. It requires both individual epiphanies and inventiveness as well as a sense of a novel aesthetic. It requires woodworking skills as well as an insightful utilisation of digitalisation and new industrial methods. It also requires collaboration between designers, builders and the industry and, above all, aware and quality-conscious clients.

* The project is presented in the Future Finland Built of Wood series.