How did a Finnish settlement cope with the transformation into a Soviet sovkhoz population centre?

Finnish Heritage Agency, Ethnology Picture Collection / Aarne Roiha

The central settlement of Kurkijoki municipality in the former Finnish territory was to become, in the Soviet Union, a modern socialist agro-city. However, it still retains some of the characteristics of small Finnish wooden towns. Architect Netta Böök’s doctoral thesis examined what happened to the settlement after the cession of territory following the Winter and Continuation Wars from the architectural history perspective.

This year marks 80 years of Finland's cession of territory to the Soviet Union. Thirty-three years ago, in December 1991, the socialist superpower collapsed. Then, we future architects got to visit the former Finnish towns of Vyborg and Sortavala and see their magnificent Finnish functionalism.

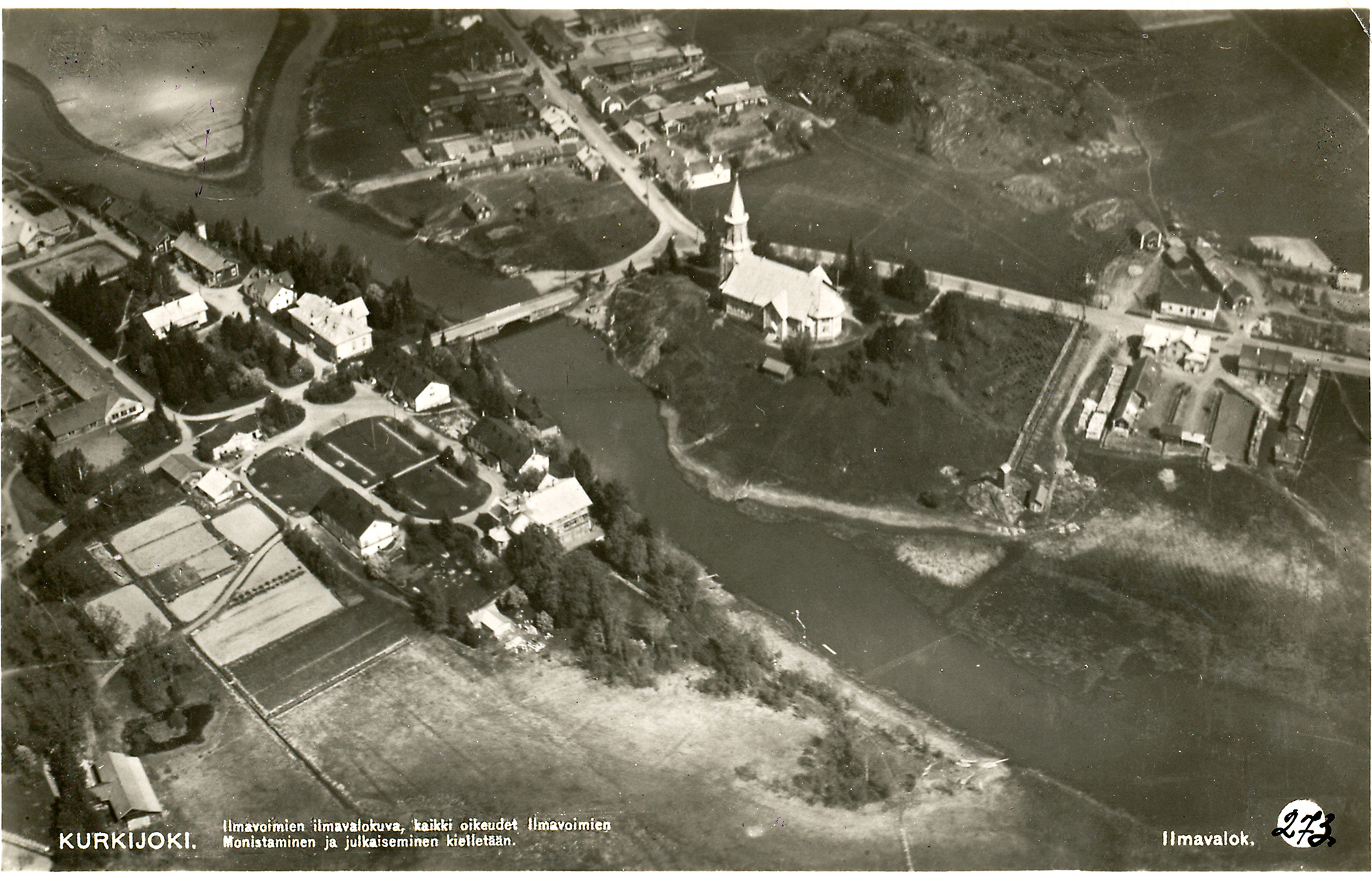

I was interested in what had happened to the major Finnish settlements in the countryside. Many had suffered greatly during the war years, others during the Soviet years. But the central settlement of Kurkijoki municipality on the western shore of Lake Ladoga survived it all. After the end of the Winter War in March 1940, the municipality was annexed to Soviet Karelia, then back to Finland in August 1941 and again to Soviet Karelia in September 1944. The population and the social and economic structures changed just as many times.

And yet, at the beginning of the 21st century, the settlement's main street felt at times as if you were walking in 1930s Finland, while the side streets brought you back to the Soviet Union. The combination felt strange. Was it perhaps the result of conscious planning?

Cover image: Lenin street in 1971. The former bookstore (left) has been transformed into a collective dormitory and the municipal doctor’s house into smaller flats. photo: Finnish Heritage Agency, Ethnology Picture Collection / Aarne Roiha

A model socialist village?

In the Soviet Union, the Communist Party, as part of its agricultural policy, defined what the countryside and its architecture should be like. The architectural design work included both urban settlements and the dwellings of agricultural workers.

At the time of Kurkijoki’s cession, it was a compact, small-town-like village with commerce shaped by the Finnish building code. The streets were lined with boarded and painted wooden houses. The wooden church was designed by F. A. Sjöström and the Kurkijoki agricultural college and training farm on the opposite bank of the river contained works of Theodor Höijer and Lars Sonck, all top-rank architects of their time. The town hall and the orthodox church were drawn by building masters.

In the Soviet Union, the village had to be adapted to the needs of socialism. How did this happen?

The Agricultural Cabinet of the Academy of Architecture had defined what a good socialist village would be like. Similarly to a socialist town, it was to be divided into functional zones, with agricultural production in its own zone. The village would include schools, kindergartens and hospitals, and the landmark would be a club or culture house, the main symbolic building of Soviet culture.

The ideal reflected the idea, inherited from Karl Marx, of eliminating the distinction between rural and urban areas, but it can also be seen as a reflection of how underdeveloped the Soviet countryside was in many places. Indeed, one can argue that the village of Kurkijoki almost fulfilled the requirements of a socialist village as such. It had practically all the services, or at least the facilities, required in a modern socialist settlement. The actual settlement was naturally suited as a residential and service zone, and the surroundings of the agricultural college as a production area. In addition, the buildings were clustered along a single main street, which was also in line with the recommendations of the 1939 Conference on Rural Architecture.

Hence, it was no wonder that Kurkijoki was transformed into an administrative centre and a state-supported large-scale farm, a sovkhoz, was set up there and became the settlement's main employer.

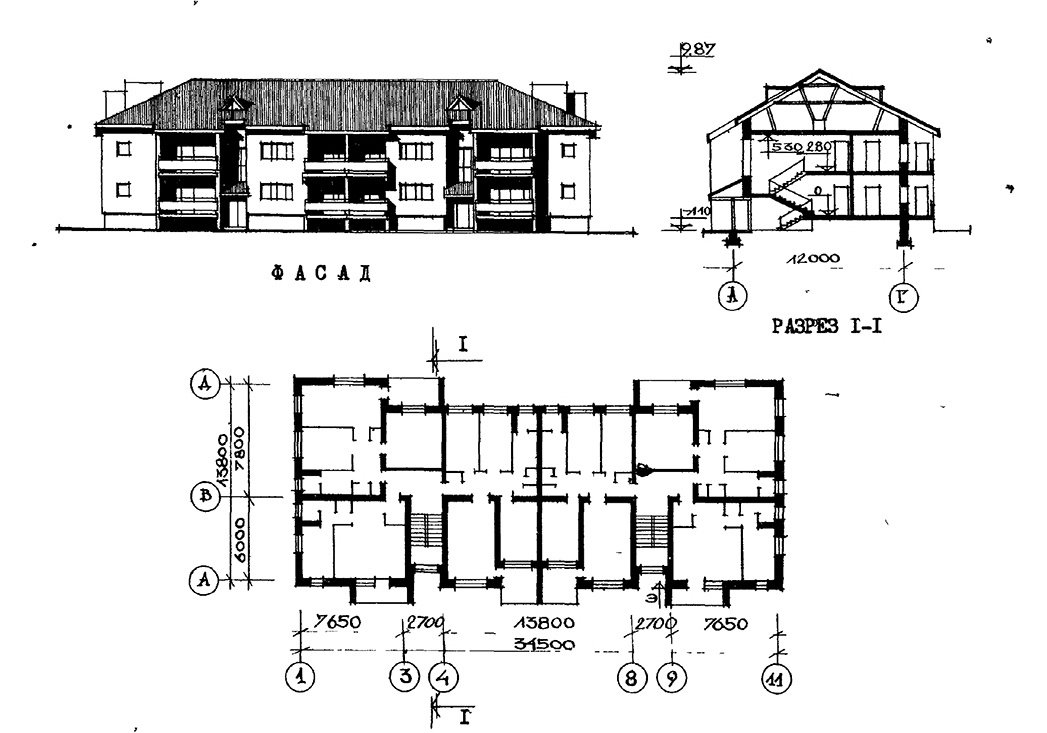

Finnish houses were a vital resource, even if they were perceived as somewhat alien. They seemed suspiciously like products of capitalism and were at odds with socialism's collective way of life. So they were split up into several apartments, and in addition, 'Stalin's barracks' were built: wooden two-storey multi-family type houses designed by the central planning offices. These houses were not presented in architectural publications, but with a log frame, they were an affordable solution for the cold northern conditions.

This is how Kurkijoki was built until 1968.

Or a modern semi-urban agro-town?

A persistent problem in the Soviet Union was the low productivity of agriculture. This was largely due to collectivisation, but in the 1960s, the problem was tackled through urban planning. Productivity was thought to improve by creating urban living conditions in rural areas and recruiting agricultural specialists. In 1968, architects across the country were given a new task: to create modern model agriculture townships that have often been called agro-towns. The best were rewarded.

It is not known whether model townships were designed on the territory ceded by Finland, but in 1975, a major housing development and planning scheme was drawn up for the Kurkijoki settlement – at the Central research and design institute of standard and experimental rural construction in Moscow. A multidisciplinary team of the country's top experts was involved with high ambitions. The township was to have blocks of flats and terraced houses, a new house of culture, everyday services, municipal engineering and parks.

The old building stock transformed from a resource into a burden that had to be mainly demolished.

The 1975 plan shows that ambitious modernisation plans could be drawn up for central settlements in the former Finnish countryside. The extensive demolition and the use of type house drawings were actually not significantly different from, for example, Finnish suburban and urban building practices. The most significant difference was in the quality of materials and construction work. In the Soviet Union, architects did not supervise the construction of standard buildings, and contractors had little responsibility for the final result.

Indeed, one of the aspects highlighted in my research was the different roles of architects in the Finnish and Soviet countryside. During the Finnish period, the most important buildings in Kurkijoki were individually designed. Quality was sought even when the country was at war by distributing type drawings optimised by architects to self-builders. The municipal building master steered private construction, and the drawings for a new school building were drafted by an architect.

Soviet architects, on the other hand, were government officials who implemented the party's visions. This included providing equal conditions for citizens, which were sought to be ensured by using type drawings honed for years by the central design offices and used throughout the Soviet Union. Not a single building based on individual drawings was erected in Kurkijoki.

Or was it, after all, a paradise lost?

Then why does the Kurkijoki settlement still in the 21st century look almost Finnish in places?

Because the reform plan was never brought to fruition. Due to a lack of resources and housing, old buildings could not be demolished, and new ones were only built on empty land, often outside the planning scheme.

On a Soviet scale, the Kurkijoki case is just one example of the failure to modernise the countryside. At the same time, the transformation of the settlement during the Soviet era revealed a contradiction between rural development goals and the inhabitants’ experience. For the early Soviet settlers, the Finnish village with its well-built houses had been a 'paradise' that was then gradually lost.

Netta Böök received her doctorate from the Department of Architecture of Aalto University’s School of Arts and Design on 1 December 2023. The opponent in the public examination was Professor Maria Lähteenmäki of the University of Eastern Finland’s Karelian Research Institute, and the custos was Professor Panu Savolainen of Aalto University.

Netta Böök: Talot pysyvät, ihmiset vaihtuvat. Sosialistisen yhteiskunnan rakentaminen entisessä suomalaisessa Kurkijoen kirkonkylässä Neuvostoliitossa. Bidrag till kännedom av Finlands natur och folk 224. Societas Scientiarum Fennica, Helsinki 2023.

The doctoral thesis has been published in Finnish with a summary in English and Russian. The title translates to Houses stay, people move. Building a socialist society in a former Finnish settlement in Kurkijoki in the Soviet Union. The printed book is sold by Tiedekirja, and a PDF version can be downloaded from The Finnish Society of Sciences and Letters website.